Definition

Bipolar disorder — sometimes called manic-depressive disorder — is associated with mood swings that range from the lows of depression to the highs of mania. When you become depressed, you may feel sad or hopeless and lose interest or pleasure in most activities. When your mood shifts in the other direction, you may feel euphoric and full of energy. Mood shifts may occur only a few times a year, or as often as several times a day. In some cases, bipolar disorder causes symptoms of depression and mania at the same time.

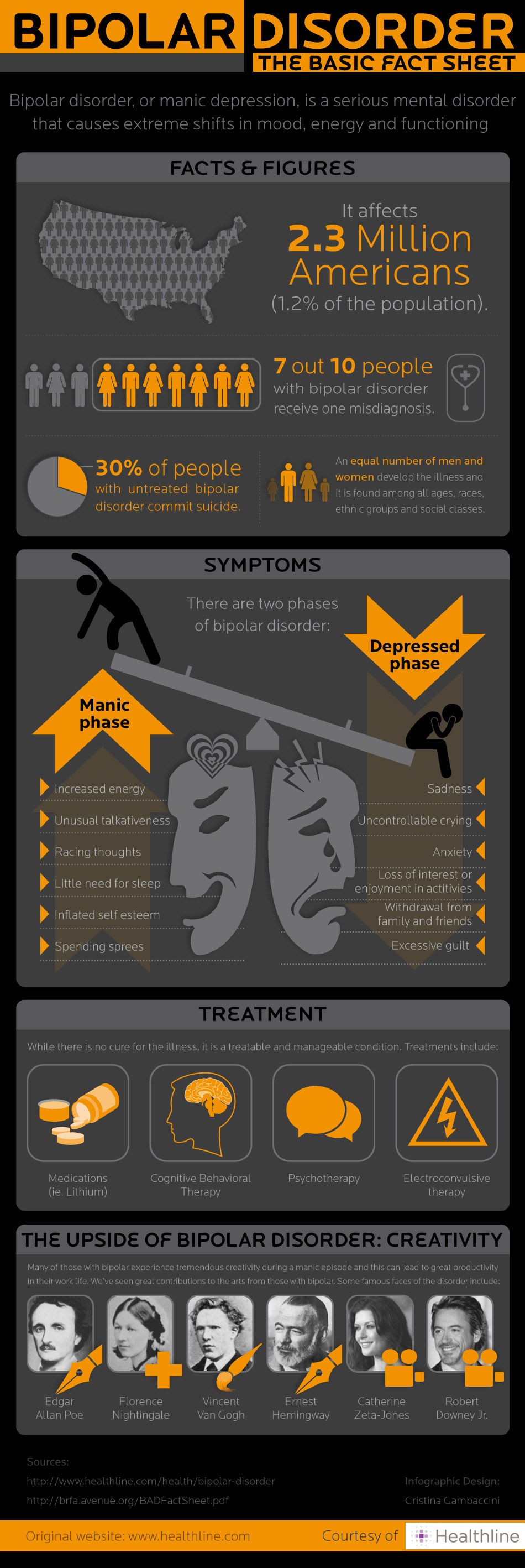

What Is Bipolar Disorder?

Bipolar disorder, also known as manic-depressive illness, is a brain disorder that causes unusual shifts in mood, energy, activity levels, and the ability to carry out day-to-day tasks. Symptoms of bipolar disorder are severe. They are different from the normal ups and downs that everyone goes through from time to time. Bipolar disorder symptoms can result in damaged relationships, poor job or school performance, and even suicide. But bipolar disorder can be treated, and people with this illness can lead full and productive lives.

Causes

Scientists are studying the possible causes of bipolar disorder. Most scientists agree that there is no single cause. Rather, many factors likely act together to produce the illness or increase risk.

Genetics

Bipolar disorder tends to run in families. Some research has suggested that people with certain genes are more likely to develop bipolar disorder than others. Children with a parent or sibling who has bipolar disorder are much more likely to develop the illness, compared with children who do not have a family history of bipolar disorder. However, most children with a family history of bipolar disorder will not develop the illness.

Technological advances are improving genetic research on bipolar disorder. One example is the launch of the Bipolar Disorder Phenome Database, funded in part by NIMH. Using the database, scientists will be able to link visible signs of the disorder with the genes that may influence them.

Scientists are also studying illnesses with similar symptoms such as depression and schizophrenia to identify genetic differences that may increase a person's risk for developing bipolar disorder. Finding these genetic "hotspots" may also help explain how environmental factors can increase a person's risk.

But genes are not the only risk factor for bipolar disorder. Studies of identical twins have shown that the twin of a person with bipolar illness does not always develop the disorder, despite the fact that identical twins share all of the same genes. Research suggests that factors besides genes are also at work. It is likely that many different genes and environmental factors are involved. However, scientists do not yet fully understand how these factors interact to cause bipolar disorder.

Brain structure and functioning

Brain-imaging tools, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), allow researchers to take pictures of the living brain at work. These tools help scientists study the brain's structure and activity.

Some imaging studies show how the brains of people with bipolar disorder may differ from the brains of healthy people or people with other mental disorders. For example, one study using MRI found that the pattern of brain development in children with bipolar disorder was similar to that in children with "multi-dimensional impairment," a disorder that causes symptoms that overlap somewhat with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. This suggests that the common pattern of brain development may be linked to general risk for unstable moods.

Another MRI study found that the brain's prefrontal cortex in adults with bipolar disorder tends to be smaller and function less well compared to adults who don't have bipolar disorder. The prefrontal cortex is a brain structure involved in "executive" functions such as solving problems and making decisions. This structure and its connections to other parts of the brain mature during adolescence, suggesting that abnormal development of this brain circuit may account for why the disorder tends to emerge during a person's teen years. Pinpointing brain changes in youth may help us detect illness early or offer targets for early intervention.

The connections between brain regions are important for shaping and coordinating functions such as forming memories, learning, and emotions, but scientists know little about how different parts of the human brain connect. Learning more about these connections, along with information gained from genetic studies, helps scientists better understand bipolar disorder. Scientists are working towards being able to predict which types of treatment will work most effectively.

Signs & Symptoms

People with bipolar disorder experience unusually intense emotional states that occur in distinct periods called "mood episodes." Each mood episode represents a drastic change from a person’s usual mood and behavior. An overly joyful or overexcited state is called a manic episode, and an extremely sad or hopeless state is called a depressive episode. Sometimes, a mood episode includes symptoms of both mania and depression. This is called a mixed state. People with bipolar disorder also may be explosive and irritable during a mood episode.

Extreme changes in energy, activity, sleep, and behavior go along with these changes in mood. Symptoms of bipolar disorder are described below.

Symptoms of mania or a manic episode include:

|

Symptoms of depression or a depressive episode include:

|

Mood Changes

Behavioral Changes

|

Mood Changes

Behavioral Changes

|

Bipolar disorder can be present even when mood swings are less extreme. For example, some people with bipolar disorder experience hypomania, a less severe form of mania. During a hypomanic episode, you may feel very good, be highly productive, and function well. You may not feel that anything is wrong, but family and friends may recognize the mood swings as possible bipolar disorder. Without proper treatment, people with hypomania may develop severe mania or depression.

Bipolar disorder may also be present in a mixed state, in which you might experience both mania and depression at the same time. During a mixed state, you might feel very agitated, have trouble sleeping, experience major changes in appetite, and have suicidal thoughts. People in a mixed state may feel very sad or hopeless while at the same time feel extremely energized.

Sometimes, a person with severe episodes of mania or depression has psychotic symptoms too, such as hallucinations or delusions. The psychotic symptoms tend to reflect the person's extreme mood. For example, if you are having psychotic symptoms during a manic episode, you may believe you are a famous person, have a lot of money, or have special powers. If you are having psychotic symptoms during a depressive episode, you may believe you are ruined and penniless, or you have committed a crime. As a result, people with bipolar disorder who have psychotic symptoms are sometimes misdiagnosed with schizophrenia.

People with bipolar disorder may also abuse alcohol or substances, have relationship problems, or perform poorly in school or at work. It may be difficult to recognize these problems as signs of a major mental illness.

Bipolar disorder usually lasts a lifetime. Episodes of mania and depression typically come back over time. Between episodes, many people with bipolar disorder are free of symptoms, but some people may have lingering symptoms.

Who Is At Risk?

Bipolar disorder often develops in a person's late teens or early adult years. At least half of all cases start before age 25. Some people have their first symptoms during childhood, while others may develop symptoms late in life.

Diagnosis

Doctors diagnose bipolar disorder using guidelines from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). To be diagnosed with bipolar disorder, the symptoms must be a major change from your normal mood or behavior. There are four basic types of bipolar disorder:

- Bipolar I Disorder—defined by manic or mixed episodes that last at least seven days, or by manic symptoms that are so severe that the person needs immediate hospital care. Usually, depressive episodes occur as well, typically lasting at least 2 weeks.

- Bipolar II Disorder—defined by a pattern of depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes, but no full-blown manic or mixed episodes.

- Bipolar Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (BP-NOS)—diagnosed when symptoms of the illness exist but do not meet diagnostic criteria for either bipolar I or II. However, the symptoms are clearly out of the person's normal range of behavior.

- Cyclothymic Disorder, or Cyclothymia—a mild form of bipolar disorder. People with cyclothymia have episodes of hypomania as well as mild depression for at least 2 years. However, the symptoms do not meet the diagnostic requirements for any other type of bipolar disorder.

A severe form of the disorder is called Rapid-cycling Bipolar Disorder. Rapid cycling occurs when a person has four or more episodes of major depression, mania, hypomania, or mixed states, all within a year. Rapid cycling seems to be more common in people who have their first bipolar episode at a younger age. One study found that people with rapid cycling had their first episode about 4 years earlier—during the mid to late teen years—than people without rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Rapid cycling affects more women than men. Rapid cycling can come and go.

When getting a diagnosis, a doctor or health care provider should conduct a physical examination, an interview, and lab tests. Currently, bipolar disorder cannot be identified through a blood test or a brain scan, but these tests can help rule out other factors that may contribute to mood problems, such as a stroke, brain tumor, or thyroid condition. If the problems are not caused by other illnesses, your health care provider may conduct a mental health evaluation or provide a referral to a trained mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist, who is experienced in diagnosing and treating bipolar disorder.

The doctor or mental health professional should discuss with you any family history of bipolar disorder or other mental illnesses and get a complete history of symptoms. The doctor or mental health professional should also talk to your close relatives or spouse about your symptoms and family medical history.

People with bipolar disorder are more likely to seek help when they are depressed than when experiencing mania or hypomania. Therefore, a careful medical history is needed to assure that bipolar disorder is not mistakenly diagnosed as major depression. Unlike people with bipolar disorder, people who have depression only (also called unipolar depression) do not experience mania.

Bipolar disorder can worsen if left undiagnosed and untreated. Episodes may become more frequent or more severe over time without treatment. Also, delays in getting the correct diagnosis and treatment can contribute to personal, social, and work-related problems. Proper diagnosis and treatment help people with bipolar disorder lead healthy and productive lives. In most cases, treatment can help reduce the frequency and severity of episodes.

Substance abuse is very common among people with bipolar disorder, but the reasons for this link are unclear. Some people with bipolar disorder may try to treat their symptoms with alcohol or drugs. However, substance abuse may trigger or prolong bipolar symptoms, and the behavioral control problems associated with mania can result in a person drinking too much.

Anxiety disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and social phobia, also co-occur often among people with bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder also co-occurs with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which has some symptoms that overlap with bipolar disorder, such as restlessness and being easily distracted.

People with bipolar disorder are also at higher risk for thyroid disease, migraine headaches, heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and other physical illnesses. These illnesses may cause symptoms of mania or depression. They may also result from treatment for bipolar disorder.

Treatments

Bipolar disorder cannot be cured, but it can be treated effectively over the long-term. Proper treatment helps many people with bipolar disorder—even those with the most severe forms of the illness—gain better control of their mood swings and related symptoms. But because it is a lifelong illness, long-term, continuous treatment is needed to control symptoms. However, even with proper treatment, mood changes can occur. In the NIMH-funded Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study—the largest treatment study ever conducted for bipolar disorder—almost half of those who recovered still had lingering symptoms. Having another mental disorder in addition to bipolar disorder increased one's chances for a relapse. See STEP-BD for more information.

Treatment is more effective if you work closely with a doctor and talk openly about your concerns and choices. An effective maintenance treatment plan usually includes a combination of medication and psychotherapy.

Medications

Different types of medications can help control symptoms of bipolar disorder. Not everyone responds to medications in the same way. You may need to try several different medications before finding ones that work best for you.

Keeping a daily life chart that makes note of your daily mood symptoms, treatments, sleep patterns, and life events can help you and your doctor track and treat your illness most effectively. If your symptoms change or if side effects become intolerable, your doctor may switch or add medications.

The types of medications generally used to treat bipolar disorder include mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics, and antidepressants. For the most up-to-date information on medication use and their side effects, contact the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Mood stabilizers are usually the first choice to treat bipolar disorder. In general, people with bipolar disorder continue treatment with mood stabilizers for years. Lithium (also known as Eskalith or Lithobid) is an effective mood stabilizer. It was the first mood stabilizer approved by the FDA in the 1970's for treating both manic and depressive episodes.

Anticonvulsants are also used as mood stabilizers. They were originally developed to treat seizures, but they also help control moods. Anticonvulsants used as mood stabilizers include:

- Valproic acid or divalproex sodium (Depakote), approved by the FDA in 1995 for treating mania. It is a popular alternative to lithium. However, young women taking valproic acid face special precautions.

- Lamotrigine (Lamictal), FDA-approved for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. It is often effective in treating depressive symptoms.

- Other anticonvulsant medications, including gabapentin (Neurontin), topiramate (Topamax), and oxcarbazepine (Trileptal).

Valproic acid, lamotrigine, and other anticonvulsant medications have an FDA warning. The warning states that their use may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. People taking anticonvulsant medications for bipolar or other illnesses should be monitored closely for new or worsening symptoms of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, or any unusual changes in mood or behavior. If you take any of these medications, do not make any changes to your dosage without talking to your doctor.

What are the side effects of mood stabilizers?

Lithium can cause side effects such as:

- Restlessness

- Dry mouth

- Bloating or indigestion

- Acne

- Unusual discomfort to cold temperatures

- Joint or muscle pain

- Brittle nails or hair.

When taking lithium, your doctor should check the levels of lithium in your blood regularly, and will monitor your kidney and thyroid function as well. Lithium treatment may cause low thyroid levels in some people. Low thyroid function, called hypothyroidism, has been associated with rapid cycling in some people with bipolar disorder, especially women.

Because too much or too little thyroid hormone can lead to mood and energy changes, it is important that your doctor check your thyroid levels carefully. You may need to take thyroid medication, in addition to medications for bipolar disorder, to keep thyroid levels balanced.

Common side effects of other mood stabilizing medications include:

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

- Heartburn

- Mood swings

- Stuffed or runny nose, or other cold-like symptoms.

These medications may also be linked with rare but serious side effects. Talk with your doctor or a pharmacist to make sure you understand signs of serious side effects for the medications you're taking. If extremely bothersome or unusual side effects occur, tell your doctor as soon as possible.

Should young women take valproic acid?

Valproic acid may increase levels of testosterone (a male hormone) in teenage girls. It could lead to a condition called polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in women who begin taking the medication before age 20. PCOS can cause obesity, excess body hair, an irregular menstrual cycle, and other serious symptoms. Most of these symptoms will improve after stopping treatment with valproic acid. Young girls and women taking valproic acid should be monitored carefully by a doctor.

Atypical antipsychotics are sometimes used to treat symptoms of bipolar disorder. Often, these medications are taken with other medications, such as antidepressants. Atypical antipsychotics include:

- Olanzapine (Zyprexa), which when given with an antidepressant medication, may help relieve symptoms of severe mania or psychosis. Olanzapine can be taken as a pill or a shot. The shot is often used for urgent treatment of agitation associated with a manic or mixed episode. Olanzapine can be used as maintenance treatment as well, even when psychotic symptoms are not currently present.

- Aripiprazole (Abilify), which is used to treat manic or mixed episodes. Aripiprazole is also used for maintenance treatment. Like olanzapine, aripiprazole can be taken as a pill or a shot. The shot is often used for urgent treatment of severe symptoms.

- Quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal) and ziprasidone (Geodon) also are prescribed to relieve the symptoms of manic episodes.

What are the side effects of atypical antipsychotics?

If you are taking antipsychotics, you should not drive until you have adjusted to your medication. Side effects of many antipsychotics include:

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness when changing positions

- Blurred vision

- Rapid heartbeat

- Sensitivity to the sun

- Skin rashes

- Menstrual problems for women.

Atypical antipsychotic medications can cause major weight gain and changes in your metabolism. This may increase your risk of getting diabetes and high cholesterol. Your doctor should monitor your weight, glucose levels, and lipid levels regularly while you are taking these medications.

In rare cases, long-term use of atypical antipsychotic drugs may lead to a condition called tardive dyskinesia (TD). The condition causes uncontrollable muscle movements, frequently around the mouth. TD can range from mild to severe. Some people with TD recover partially or fully after they stop taking the drug, but others do not.

Antidepressants are sometimes used to treat symptoms of depression in bipolar disorder. Fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), sertraline (Zoloft), and bupropion (Wellbutrin) are examples of antidepressants that may be prescribed to treat symptoms of bipolar depression.

However, taking only an antidepressant can increase your risk of switching to mania or hypomania, or of developing rapid-cycling symptoms. To prevent this switch, doctors usually require you to take a mood-stabilizing medication at the same time as an antidepressant.

What are the side effects of antidepressants?

Antidepressants can cause:

- Headache

- Nausea (feeling sick to your stomach)

- Agitation (feeling jittery)

- Sexual problems, which can affect both men and women. These include reduced sex drive and problems having and enjoying sex.

Report any concerns about side effects to your doctor right away. You may need a change in the dose or a different medication. You should not stop taking a medication without talking to your doctor first. Suddenly stopping a medication may lead to "rebound" or worsening of bipolar disorder symptoms. Other uncomfortable or potentially dangerous withdrawal effects are also possible.

Some antidepressants are more likely to cause certain side effects than other types. Your doctor or pharmacist can answer questions about these medications. Any unusual reactions or side effects should be reported to a doctor immediately.

Should women who are pregnant or may become pregnant take medication for bipolar disorder?

Women with bipolar disorder who are pregnant or may become pregnant face special challenges. Mood stabilizing medications can harm a developing fetus or nursing infant. But stopping medications, either suddenly or gradually, greatly increases the risk that bipolar symptoms will recur during pregnancy.

Lithium is generally the preferred mood-stabilizing medication for pregnant women with bipolar disorder. However, lithium can lead to heart problems in the fetus. In addition, women need to know that most bipolar medications are passed on through breast milk. The FDA has also issued warnings about the potential risks associated with the use of antipsychotic medications during pregnancy. If you are pregnant or nursing, talk to your doctor about the benefits and risks of all available treatments.

FDA Warning on Antidepressants

Antidepressants are safe and popular, but some studies have suggested that they may have unintentional effects on some people, especially in adolescents and young adults. The FDA warning says that patients of all ages taking antidepressants should be watched closely, especially during the first few weeks of treatment. Possible side effects to look for are depression that gets worse, suicidal thinking or behavior, or any unusual changes in behavior such as trouble sleeping, agitation, or withdrawal from normal social situations. For the latest information, see the FDA website .

Psychotherapy

When done in combination with medication, psychotherapy can be an effective treatment for bipolar disorder. It can provide support, education, and guidance to people with bipolar disorder and their families. Some psychotherapy treatments used to treat bipolar disorder include:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which helps people with bipolar disorder learn to change harmful or negative thought patterns and behaviors.

- Family-focused therapy, which involves family members. It helps enhance family coping strategies, such as recognizing new episodes early and helping their loved one. This therapy also improves communication among family members, as well as problem-solving.

- Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, which helps people with bipolar disorder improve their relationships with others and manage their daily routines. Regular daily routines and sleep schedules may help protect against manic episodes.

- Psychoeducation, which teaches people with bipolar disorder about the illness and its treatment. Psychoeducation can help you recognize signs of an impending mood swing so you can seek treatment early, before a full-blown episode occurs. Usually done in a group, psychoeducation may also be helpful for family members and caregivers.

In a STEP-BD study on psychotherapies, researchers compared people in two groups. The first group was treated with collaborative care (three sessions of psychoeducation over 6 weeks). The second group was treated with medication and intensive psychotherapy (30 sessions over 9 months of CBT, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, or family-focused therapy). Researchers found that the second group had fewer relapses, lower hospitalization rates, and were better able to stick with their treatment plans. They were also more likely to get well faster and stay well longer. Overall, more than half of the study participants recovered over the course of 1 year.

A licensed psychologist, social worker, or counselor typically provides psychotherapy. He or she should work with your psychiatrist to track your progress. The number, frequency, and type of sessions should be based on your individual treatment needs. As with medication, following the doctor's instructions for any psychotherapy will provide the greatest benefit.

Visit the NIMH website for more information on psychotherapy.

Other treatments

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)—For cases in which medication and psychotherapy do not work, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be useful. ECT, formerly known as "shock therapy," once had a bad reputation. But in recent years, it has greatly improved and can provide relief for people with severe bipolar disorder who have not been able to recover with other treatments.

Before ECT is administered, a patient takes a muscle relaxant and is put under brief anesthesia. He or she does not consciously feel the electrical impulse administered in ECT. On average, ECT treatments last from 30–90 seconds. People who have ECT usually recover after 5–15 minutes and are able to go home the same day.

Sometimes ECT is used for bipolar symptoms when other medical conditions, including pregnancy, make the use of medications too risky. ECT is a highly effective treatment for severely depressive, manic, or mixed episodes. But it is generally not used as a first-line treatment.

ECT may cause some short-term side effects, including confusion, disorientation, and memory loss. People with bipolar disorder should discuss possible benefits and risks of ECT with an experienced doctor.

Sleep Medications—People with bipolar disorder who have trouble sleeping usually sleep better after getting treatment for bipolar disorder. However, if sleeplessness does not improve, your doctor may suggest a change in medications. If the problems still continue, your doctor may prescribe sedatives or other sleep medications.

Herbal Supplements—In general, not much research has been conducted on herbal or natural supplements and how they may affect bipolar disorder. An herb called St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum), often marketed as a natural antidepressant, may cause a switch to mania in some people with bipolar disorder. St. John's wort can also make other medications less effective, including some antidepressant and anticonvulsant medications. Scientists are also researching omega-3 fatty acids (most commonly found in fish oil) to measure their usefulness for long-term treatment of bipolar disorder. Study results have been mixed.

Be sure to tell your doctor about all prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, or supplements you are taking. Certain medications and supplements taken together may cause unwanted or dangerous effects.

What research is NIMH doing to improve treatments for bipolar disorder?

Scientists are working to identify new targets for improving current medications or developing new treatments for bipolar disorder. In addition, NIMH researchers have made promising advances toward finding fast-acting medication treatment. In a small study of people with bipolar disorder whose symptoms had not responded to prior treatments, a single dose of ketamine—an anesthetic medication—significantly reduced symptoms of depression in as little as 40 minutes. These effects lasted about a week on average.

Ketamine itself is unlikely to become widely available as a treatment because it can cause serious side effects at high doses, such as hallucinations. However, scientists are working to understand how the drug works on the brain in an effort to develop treatments with fewer side effects and that act similarly to ketamine. Such medications could also be used for longer term management of symptoms.

In addition, NIMH is working to better understand bipolar disorder and other mental disorders by spearheading the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Project, which is an ongoing effort to map our current understanding of the brain circuitry that is involved in behavioral and cognitive functioning. By essentially breaking down mental disorders into their component pieces—RDoC aims to add to the knowledge we have gained from more traditional research approaches that focus solely on understanding mental disorders based on symptoms. The hope is that by changing the way we approach mental disorders, RDoC will help us open the door to new targets of preventive and treatment interventions.

Living With

If you know someone who has bipolar disorder, it affects you too. The first and most important thing you can do is help him or her get the right diagnosis and treatment. You may need to make the appointment and go with him or her to see the doctor. Encourage your loved one to stay in treatment.

To help a friend or relative, you can:

- Offer emotional support, understanding, patience, and encouragement

- Learn about bipolar disorder so you can understand what your friend or relative is experiencing

- Talk to your friend or relative and listen carefully

- Listen to feelings your friend or relative expresses and be understanding about situations that may trigger bipolar symptoms

- Invite your friend or relative out for positive distractions, such as walks, outings, and other activities

- Remind your friend or relative that, with time and treatment, he or she can get better.

Never ignore comments from your friend or relative about harming himself or herself. Always report such comments to his or her therapist or doctor.

How can caregivers find support?

Like other serious illnesses, bipolar disorder can be difficult for spouses, family members, friends, and other caregivers. Relatives and friends often have to cope with the person's serious behavioral problems, such as wild spending sprees during mania, extreme withdrawal during depression, or poor work or school performance. These behaviors can have lasting consequences.

Caregivers usually take care of the medical needs of their loved ones. But caregivers have to deal with how this affects their own health as well. Caregivers' stress may lead to missed work or lost free time, strained relationships with people who may not understand the situation, and physical and mental exhaustion.

It can be very hard to cope with a loved one's bipolar symptoms. One study shows that if a caregiver is under a lot of stress, his or her loved one has more trouble following the treatment plan, which increases the chance for a major bipolar episode. If you are a caregiver of someone with bipolar disorder, it is important that you also make time to take care of yourself.

How can I help myself if I have bipolar disorder?

It may be very hard to take that first step to help yourself. It may take time, but you can get better with treatment. To help yourself:

- Talk to your doctor about treatment options and progress.

- Keep a regular routine, such as going to sleep at the same time every night and eating meals at the same time every day.

- Try hard to get enough sleep.

- Stay on your medication.

- Learn about warning signs signaling a shift into depression or mania.

- Expect your symptoms to improve gradually, not immediately.

Where can I go for help?

If you are unsure where to go for help, ask your family doctor. Others who can help are listed below.

- Mental health specialists, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, or mental health counselors

- Health maintenance organizations

- Community mental health centers

- Hospital psychiatry departments and outpatient clinics

- Mental health programs at universities or medical schools

- State hospital outpatient clinics

- Family services, social agencies, or clergy

- Peer support groups

- Private clinics and facilities

- Employee assistance programs

- Local medical and/or psychiatric societies.

Bipolar disorder can be difficult to diagnose. Unless you have severe mania, in which case the signs are unmistakable, the symptoms can be hard to spot. People who have hypomania, a milder form of the manic side, may only feel more energized than usual, more confident and full of ideas, and able to get by on less sleep-and hardly anyone complains about that. You're more likely to seek help if you're suffering from depression, but then your doctor may not catch the manic side. If you're worried that you or a loved one may have bipolar disorder, the best thing to do is educate yourself about the different types of the illness and their symptoms. Here's what to look for.

Kinds of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is marked by extreme mood swings from highs to lows. These episodes can last hours, days, weeks, or months. The mood swings may even become mixed, so you might feel like crying over something upbeat. The most common kinds of bipolar disorder fall into these two categories:

Symptoms

According to the National Institute of Mental Health and other authorities, bipolar disorder may include these warning signs:

Seven Signs of Bipolar Mania:

Seven Signs of Bipolar Depression:

What to do

Call your doctor if you see any of these signs in yourself or a loved one. People with bipolar disorder often tend to deny any problems, especially during manic episodes, but don't let them fool you. Think of bipolar disorder as any other serious disease, and get help right away. With the right treatment, bipolar disorder can be controlled and the patient can go on to enjoy life.

The History of Bipolar Disorder

Aretaeus of Cappadocia began the quest into the disorder by beginning the process of detailing symptoms in the medical field as early as the 1st Century in Greece. His notations on the link between mania and depression went largely unnoticed for many centuries.

The ancient Greeks and Romans were responsible for the terms “mania” and “melancholia,” which are now the modern day manic and depressive. They even discovered that using lithium salts in baths calmed manic patients and lifted the spirits of depressedpeople. Today, lithium is a common treatment for bipolar patients.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle not only acknowledged melancholy as a condition, but thanked it as the inspiration for the great artists of his time.

It was common during this time that people across the globe were executed for having bipolar disorder and other mental conditions because as the study of medicine advanced, strict religious dogma stated these people were possessed by demons and should therefore be put to death.

In the 17th Century, Robert Burton wrote the book, The Anatomy of Melancholy, which addressed the issue of treating melancholy (non-specific depression) using music and dance as a form of treatment. While mixed with medical knowledge, the book primarily serves as a literary collection of commentary of depression, and vantage point of the full effects of depression on society. It did, however, expand deeply into the symptoms and treatments of what is now known as clinical depression.

Later that century, Theophilus Bonet published a great work titledSepuchretum, a text that drew from his experience performing 3,000 autopsies. In it, he linked mania and melancholy in a condition called “manico-melancolicus.”

This was a substantial step in diagnosing the disorder because mania and depression were most often considered separate disorders.

Centuries past, and little new was discovered about bipolar disorder until French psychiatrist Jean-Pierre Falret published an article in 1851 describing what he called “la folie circulaire,” which translates to circular insanity. The article details patients switching through severe depression and manic excitement, and is considered the first documented diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Besides the diagnosis, Falret noted the genetic connection in bipolar disorder, something medical professionals still believe to this day.

However, the history of bipolar disorder changed with Emil Kraepelin, a German psychiatrist who broke away from Sigmund Freud’s theory that society and the suppression of desires played a large role in mental illness. Kraepelin recognized biological causes of mental illnesses. He is believed to be the first person to seriously study mental illnesses.

Kraepelin’s Manic Depressive Insanity and Paranoia in 1921 detailed the difference between manic-depressive and praecox, which is now known as schizophrenia. His classification of mental disorders remains the basis used by professional associations today.

A professional classification system for mental disorders—which was important to better understand and treat conditions—has its earliest roots in the early 1950s from German psychiatrist Karl Leonhard and others.

The term “bipolar”—which means “two poles” signifying the polar opposites of mania and depression—first appeared in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagonostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in its third revision in 1980.

It was that revision that did away with the term mania to avoid calling patients “maniacs.” Now in its fourth revision with a fifth version due in 2013, the DSM is considered the leading manual for mental health professionals.

The current version of the DSM lists the following subtypes of bipolar disorder with the following diagnostic criteria:

Bipolar I Disorder

Bipolar II Disorder

Cyclothymic Disorder

Rapid-Cycling Bipolar Disorder

The DSM-V is expected to reflect “a significant reformulation in how personality disorders are identified and assessed. The change integrates disorder types with pathological personality traits and, most importantly, levels of impairment in what is known as ‘personality functioning,’” according to a press release from the American Psychiatric Association.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.